1 Introduction

In this chapter, you get to know the concept of reproducibility, different types of reproducibility and related but somewhat different concepts.

1.1 What is reproducibility?

A good definition of reproducibility is given by The Turing Way Company:

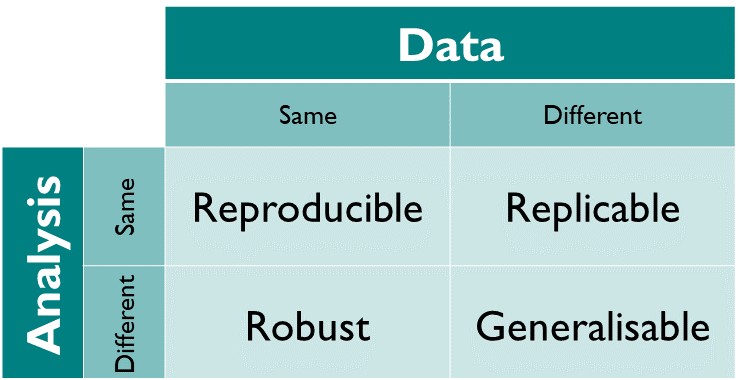

“At The Turing Way, we define reproducible research as work that can be independently recreated from the same data and the same code that the original team used. Reproducible is distinct from replicable, robust and generalisable as described in the figure below.” - The Turing Way Community (2022), chapter on Reproducibility.

We will use this conceptualization of reproducibility throughout the book. Note, that reproducibility and replicability are two different terms. Replicability is achieved when the same analysis produce similar answers among different datasets, whereas reproducibility when the same analysis produce the same answer in the same dataset. That makes reproducibility the lowest common denominator in research.

The definition above is the most common definition of reproducibility. Note, that some research areas use the terms reproducibility and replicability the other way around. Thus, in computational science, reproducibility is given when the same result is obtained when the same analyses are carried out with different data. Other areas use these terms interchangeably.

Dependent on the research area, reproducibility and replicability are used differently. In this book, we use a consistent and distinct conceptualization. Reproducibility means that the same analysis of the same data leads to the same result. Replicability means that the same analysis of different data leads to the same result.

If you look in the literature, be aware of what these terms express respective of the study you are reading.

Within this book, we limit the term reproducibility to computational entities. Thus, we mainly focus on data and code.

1.1.1 Two errors of reproducibility

As a researcher who wants to reproduce a result from a different research project, there are two main reasons why reproducibility might fail (Nosek et al. 2022). First, you may not be able to repeat the analysis that had been done before, because of data or code unavailability or the lack of information or software to recreate code. This is called a process-based reproducibility failure. Second, your reanalysis yield different results than the original report. This is called an outcome-based reproducibility failure and can happen due to an error either in the original or the reproduction study (Nosek et al. 2022).

1.2 Benefits of reproducible research

- Enhances the clarity of research processes for other researchers and yourself

- Allows other researchers to verify your results

- Increases the credibility of research findings

- Saves time in the long run by reusing methods and data

- Aids in the identification of errors and biases

- Ensures that research outputs can be used in future studies

- Promotes better documentation of research processes

- Strengthen a researcher’s reputation and career prospects

- Fosters public understanding of scientific processes

- Promotes better data management practices

- Minimizes duplication of research efforts

1.3 Current state of reproducibility

Before going deeper into the applied methods of making research reproducible, let’s have a look at how good research (psychological research) is now. The investigation into reproducibility started around 2010 with the beginning of the replication crisis. Artner et al. (2021) investigated the reproducibility of 46 articles from 2012, published in 3 different APA journals. The authors extracted 232 statistical claims and were able to reproduce 163 (70%) of the results. More recently, a study evaluated the reproducibility of research on the study level rather than the statistical result level. Hardwicke et al. (2021) investigated 25 articles of the journal Psychological Science that were published between 2014 and 2015 and awarded with OpenData Badges. Overall, 15 articles (60%) were fully reproducible, 9 of them (60%) without author involvement. Another article investigated 14 articles from an issue of the same journal five years later and tried to reproduce the results of the articles in that issue (Crüwell et al. 2023). The researchers could only exactly reproduce the results of one of the 14 articles. Three articles were essentially reproducible with minor deviations (such as typographical mistakes). Noteworthy: All of these articles were certified with an OpenData-Badge. Another study investigated 62 registered reports from the psychological literature from 2014-2018. 36 of them (58%) provided shared data and code and 21 of these 36 (58%) were reproducible (Obels et al. 2020). This evidence shows that psychological literature is far from a reproducibility ratio of 100%. However, a substantial body of studies already is reproducible.

Despite these raw findings the researchers of the above-mentioned studies also reported hindrances that weaken and opportunities that foster the reproducibility of results. Reproducibility is not easy, in fact one of the authors described the process of reproducing the results as “cumbersome and time-consuming trial-and-error work” (Artner et al. 2021, 527). Below, a list describes hindering and fostering factors for reproducible research.

- Raw and / or data not available

- Codebook / metadata not available

- Error-prone workflow of copy-pasting values from long statistical outputs

- Unclear reporting of analytic procedures

- Different versions of packages and software

- Availability of raw and tidy data

- Availability of metadata / a codebook

- Flowchart of case selection

- Data manipulation steps stored in code

- Dynamic reports (e.g. RMarkdown or Quarto)

- Co-piloting of data analysis

Maybe, some of the concepts (e.g. raw vs. tidy data) are not familiar to you. Do not worry, this book will cover all topics, explain the concepts and will provide exercises to directly apply the concepts to a research project. One exception is the Co-piloting of data analysis. It means that other colleagues reconduct your data analyses based on your shared data and code. To get the best out of this book, we recommend to find a partner with whom you work through this book.

1.4 Reproducibility in the context of open science

Reproducibility is a buzzword that is inevitably linked to OpenScience. But what is Open Science? Many associations aiming to foster OpenScience exist, however, a clear definition is rare. In their article, Lakomý, Hlavová, and Machackova (2019) referred to a book from Cribb and Sari (2010), defining OpenScience as follows:

“Open Science is a practice aiming to make scientifically generated knowledge and its method of production more accessible, applicable, transparent, and responsive to the needs of both scientists and the public.” (Lakomý, Hlavová, and Machackova 2019, 246)

Open Science policies arose not only but also because of the so-called replication crisis. In psychology, 100 original studies were replicated and the results attracted a lot of attention. The mean effect size of the replicated studies was half the magnitude of the original effect sizes and only 36% of the replications had significant results compared to 97% of the original studies (Open Science Collaboration 2015). Psychology was not the only research area failing to replicate their studies. For example, cancer research also found theirselves in a crisis facing a thorough replication crisis (Begley and Ellis 2012). As a result, many initiatives and institutions arose to enhance the credibility of research (e.g. Center for OpenScience, ORION, and many more). This comprised not only replicability of studies but the whole research process. Thus, reproducibility is a feature of this research process. Nowadays, policies aim to not only make research open, but also a variety of other topics which are disclosed in Figure 1.2 including educational materials. This is also the reason why this Repro-Book is published online without any restrictions. As the title suggests, this book mainly focuses on computational reproducibility. However, on our way to a reproducible research project, we will tangent many topics related to OpenScience.

1.5 What this book is not about

Open Science is a huge movement with many aspects, that we cannot cover completely in this book. Reproducibility is one important aspect for striving to open science, but many topics are still left.

1.5.1 Questionable Research Practices (QRPs)

Questionable research practices (QRPs) have gained increasing attention since a popular article by John, Loewenstein, and Prelec (2012). We acknowledge the variety of QRPs and the need to face the issues raised by the authors, but that topic can fill another full book. If you feel engaged to learn more about QRPs, we recommend to read the article and the embedded references.

1.5.2 Pre-registration

Pre-registrations have become popular as one answer to QRPs. However, even pre-registered studies can be irreproducible when data and code is not findable, accessible or understandable. In turn, a fully reproducible research project does not necessarily have to be pre-registered. Both contribute in their own way to open science. If you want to pre-register your study, we recommend https://aspredicted.org or https://osf.io. If you want to learn more about pre-registration, we recommend the website of the Center for Open Science.

1.5.3 Statistics

Many aspects of this book will deal with R and RStudio, which are powerful tools for statistical programming. However, this book requires almost no statistical knowledge. You might find some t-tests or something similar in code-examples (see Section 7.5). The purpose of the book is not to increase your statistical knowledge and skills; the purpose of the book is to make your research more reproducible. If you want to learn more about statistics, we recommend this free E-book by Danielle Navarro. If you prefer an analogous book, we recommend Discovering statistics using R by Andy Field.

1.5.4 Programming

The same applies to programming as to statistics. You will not learn anything new on purpose about a programming language. However, you will learn concepts derived from programming that benefits your research. Thus, some parts of the book seem quite technical. Nevertheless, these technical parts aim to make your research more robust and less error-prone regarding reproducibility.

1.6 References

We would like to express our gratitude to the following resources which have been essential in shaping this chapter. We recommend these references for further reading.

| Authors | Title | Website | License | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John, Loewenstein, and Prelec (2012) | Measuring the Prevalence of Questionable Research Practices With Incentives for Truth Telling | |||

| Lakomý, Hlavová, and Machackova (2019) | Open Science and the Science-Society Relationship | |||

| Nosek et al. (2022) | Replicability, Robustness, and Reproducibility in Psychological Science | |||

| The Turing Way Community (2022) | Chapter on Reproducibility | CC-BY-4.0 |